Is the future of cities in the trees?

- Sep 18, 2022

- 10 min read

Startups and scientists are planting the seeds for timber cities

Amid all of the genetic engineering, lab grown foods, and other technologies boosted by President Biden’s National Biotechnology and Biomanufacturing Initiative, mass timber might not be the most advanced, but (knock on wood) it could be one of the most salient investments made to decarbonize urban environments.

Launched last week, the push for biotech funding is the latest sign that the federal government is moving to enact Biden’s executive order to strengthen bio-economic supply chains, improve health outcomes, and reduce carbon emissions.

Buried deep in the White House fact sheet of bio-this and bio-that are two little words that can easily get glossed over: mass timber.

“These regional investments will… better utilize mass timber to accelerate affordable housing production and restore forest health,” the fact sheet reads, “expanding opportunities to underserved and historically excluded communities.” The investment is a part of the “foster innovation” initiative. But it prompts the question: how in the world can scaling wood make housing affordable and restore forest health?

It's a case of missing the forest for the trees.

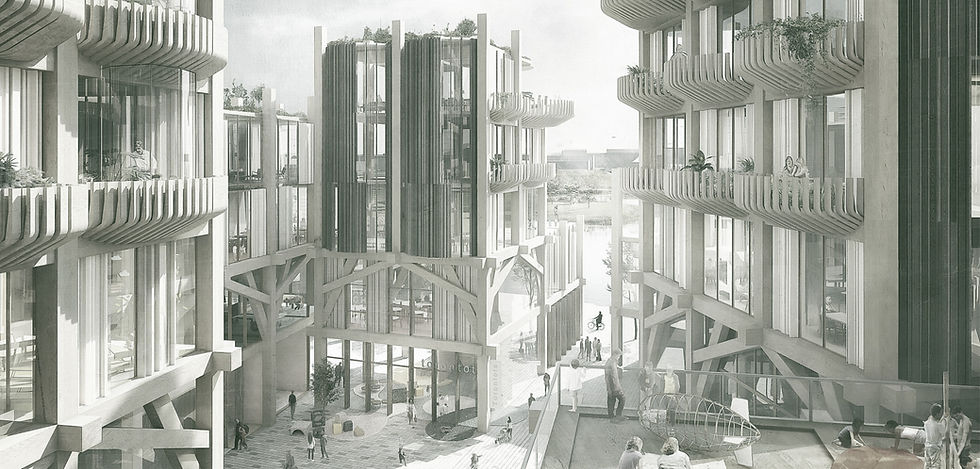

Google “futuristic city” and most images that pop up are skylines silhouetted with sleek steel-blue and white buildings and cyberpunk neon night lights. The images are complete with flying (electric) cars, bullet trains, and green-walled high-rises. Yet, when a majority of these sci-fi skyscrapers are engineered with materials like concrete and steel (typically made with high emitting processes) it could lead one to reimagine what the future’s techno (and climate-conscious) cities look like.

To the White House, startups across the world, and researchers at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), those cities could be built with timber.

The PIK recently published a study in Nature Communications confirming that a vast amount of emissions could be avoided if wood replaces conventional steel and concrete to meet growing urban housing needs.

How much could emissions could timber buildings reduce? More than 100 billion tons of CO2 until 2100. That number represents about 10% of the remaining carbon budget we must avoid emitting for the 2-degree Celsius climate target, as set by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The study hinges on the point that as global temperatures climb, so do global populations. And more people typically equates to more emissions.

"More than half the world's population currently lives in cities, and by 2100 this number will increase significantly. This means more homes will be built with steel and concrete, most of which have a serious carbon footprint," Abhijeet Mishra, PIK researcher and lead author of the study, said. "But we have an alternative: We can house the new urban population in mid-rise buildings -- that is 4 to 12 stories -- made out of wood."

Ahead of the White House’s wide-scale initiative, Oregon received $41.4 million for mass timber production. In December of 2021, Portland-based Mass Timber Coalition was among 60 finalists for $1 billion in economic grants. Tied to the coronavirus relief package, winning coalitions could shape manufacturing, clean energy, and life science hubs across the country. Earlier this month, Mass Timber Coalition announced itself a winner.

The money, awarded from the “Build Back Better Regional Challenge” will go toward advancing wood production in the accordingly named Beaver State. Just as beavers use wood to form dams and lodge houses, the money put toward mass timber is aimed at housing and forest restoration.

A few years ago, mass timber marked a shift in the construction world. In 2020, Vox called the material “The hottest thing in architecture this century. “ It’s “wood, but like Legos,” the publication wrote.

Vox’s coverage came as Norway’s Mjøstårnet finished construction as the tallest timber building in the world. Mjøstårnet, meaning “Tower of Mjösa,” stands at 280 feet surrounded by farmland, above the picturesque Mjøsa lake, and against a scenic backdrop of mountains. The 18-story structure contains apartments, office space, and the felicitously named Hotel Wood.

Sometimes dubbed “plyscrapers,” these buildings use what’s known as “mass timber,” where conifers like spruce, firs, and pine are glued together to create beams, columns, and deckings to construct buildings much like a giant’s Lego set.

Mjösa Tower marked a resurgence in the wood rebellion and investments in Oregon is only the latest addition.

Leading up to 2020, a slew of mass timber developments popped up around the world in places like London and Vancouver. The U.S. was quick to catch on. An 80-story wooden tower called the River Beech is proposed in Chicago. Recently built projects have opened in Atlanta and Minneapolis.

Overseas, companies like Metsä Wood aim their mass timber construction at urban projects across Europe in places like Amsterdam, Finland, and Berlin.

They’re not alone. France’s Woodoo makes wood alternatives to concrete, glass, and metals (and soon fabric and pulp) using cut wood that would otherwise go unused. The goal, they say, is to help create “tomorrow’s cities.”

In the U.S., B.J. Siegel, the co-founder of Juno and one of the designers of the original Apple store, has raised at least $32 million to make mass-timber construction a thing -- starting with multi-tenant apartments in Austin.

Carbon12, an eight-story condominium building in Portland, Oregon, made of glass and timber, had a similar tagline of “Building for the Future” when it opened in 2018 But in 2022, Carbon12’s 2018 development is far from the latest in Portland’s mass timber news.

Curtis Robinhold, executive director of the Port of Portland, a huge beneficiary of the Mass Timber Coalition's federal winnings, told Oregon Live, that the manufacturing facility will eventually produce about 2,000 modular homes a year. Construction will start in the next two years and by 2026, the Port of Portland facility will be producing units.

The influx of government funds through the Build Back Better initiatives pay close attention to rural, Tribal, and low-income communities, as well as communities that previously relied on coal for job opportunities. Mass timber fits into this goal well because light-frame multifamily housing mass timber can provide is not only affordable but safe.

According to a 2020 report by the Housing Coalition, units built at 6 and 12 stories using mass timber, as opposed to steel or concrete, are in high demand to meet a critical social, economic, cultural, and political problem: housing. “The current situation calls out for achievable, repeatable, affordable, durable, energy-efficient, and natural housing solutions for those in greatest need, and mass timber can provide that solution,” the report reads.

The Housing Coalition's proposition is validated by PIK's research. On top of the affordable housing problem it aims to solve, mass timber can, in tandem, work to mitigate climate change. This mitigation would be done by 1) weaning the construction industry off of concrete and steel and 2) making cities into essentially “carbon sinks.”

Concrete is the most widely used building material in the world, but with a colossal carbon footprint, concrete production is responsible for at least 8% of global greenhouse emissions. Because it’s so long-lasting, however, concrete structures and buildings are, in many ways, ideal for climate-resilient construction.

Researchers and startups have been figuring out ways to decarbonize the material’s carbon-intensive production such as reducing production temperature to lower energy usage, using low-carbon fuels as opposed to fossil fuels, going electric, or pumping captured CO2 into the concrete itself.

Second only to water, concrete is the most consumed substance in the world, totaling 30 billion tons used annually. The material has been climbing faster than both steel and wood production.

Still, with the iron and steel industry occupying 7% of global emissions, on par with concrete, it’s an industry we desperately need to decarbonize. Each year over 1500 million tons of steel are produced. Of the half that goes to the construction industry, 60% is used in buildings.

Separately, the carbon intensity of the steel industry is falling, but not by nearly enough. Punctuated with a glaring “not on track” marking in its most recent report, the International Energy Agency (IEA) states that substantial cuts will be needed to cut steel’s energy demand and CO2 emissions in the next 8 years in order to meet the net-zero-by-2050 scenario.

Yet, energy efficiency improvements will soon be exhausted, the report says, so innovation for low-emissions processes has to take place in the next decade.

To the researchers of the PIK study, that innovation is wood. Wood is a renewable resource that carries the lowest carbon footprint of any comparable building material.

"Production of engineered wood releases much less CO2 than production of steel and cement," Mishra said. "Engineered wood also stores carbon, making timber cities a unique long-term carbon sink -- by 2100, this could save more than 100 gigatons of additional CO2 emissions, equivalent to 10% of the remaining carbon budget for the 2°C target."

According to Inside Climate, Mishra and his team were inspired by an earlier paper written by their colleagues that analyzed buildings as carbon sinks. A carbon sink is anything that absorbs more carbon from the atmosphere than it releases. Forests and oceans are naturally, the world’s largest carbon sinks. Proponents of timber cities, propose using forests as part of the “built environment,” effectively giving urban habitats the sequestering power of forests.

When it's finished later this summer, Milwaukee’s Ascent, a 25-story apartment building, will double as a carbon sink.

“Building Ascent with mass timber, as opposed to post-tension concrete, is the equivalent of taking 2,400 cars off the road for a year,” Ascent’s team told NBC News. When it’s done, Ascent will best Norway’s Mjösa Tower as the tallest timber building in the world, beating the building by 4 feet.

The goal of mass timber propositions is to repeat Ascent over and over, effectively making the country’s growing metropolises into Timber Cities.

PIK’s research revealed that in order to meet urban housing needs we would need a lot of trees; an estimated 555,000 square miles of additional plantations.

That’s about the size of a Southern super-state composed of Texas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana covered entirely in trees. And that number is on top of the tree farms covering 505,000 square miles that exist globally today.

Considering the massive amounts of concrete and steel used annually by the construction industry, the researchers analyzed how the theoretical additional timber demand would be met, answering questions like “How would this impact food production?” “What about biodiversity?” “Could trees grow quickly enough to meet our needs?” and “Where on Earth would 550,000 new plantations go?”

Plus, the idea of timber cities presents a slew of other logistical questions concerning present climate disasters like wildfires, droughts, and earthquakes, and the risk of poor forest management and deforestation.

However, the idea of timber cities as an objective is not a shot in the dark. PIK’s study builds on logs and logs of pre-existing research.

Starting with the basics, despite being made of wood, mass timber is both strong and notoriously hard to ignite.

The most common form of mass timber is cross-laminated timber or CLT. The lumber boards of CLT are about a foot thick and can be as large as 18 by 48 feet, though most are 10 by 40.

They were first developed in Austria in the 1990s, where softwood forestry is extremely common. Due to slabs’ size, CLT is as solid as concrete or brick and can match or exceed concrete and steel performance. Thus, in the early 2000s, it spread across Europe like… wildfire.

In the U.S., flimsy stick-framed 2x4 plywood buildings were once the typical wood structure. Rightfully associated with fire, they were the culprit of huge disasters like The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 and have gone up in flames due to wildfires in California. So why would a place like Chicago want to try wood again? It’s hard to light them ablaze.

While the outer layer of timber predictably chars, the interior shields and effectively self-extinguishes. CLT passes fire testing and blast testing by the U.S. Forest Service and Fire Protection Research Foundation with flying colors.

The benefits of CLT don’t end at its fire resistance.

CLT sequesters carbon at a rate of roughly 1:1, where 1 cubic meter of CLT wood sequesters 1.1 tons of carbon. In addition to the mass reduction of carbon emissions presented by mass timber, CLT also allows buildings to be constructed faster, equating to lower labor costs and less waste.

An industry report posits that they are “25% faster to construct than concrete buildings and require 90% less construction traffic.” To top it off, test after test after test after test shows that they perform remarkably well in earthquakes.

“Our study underlines that urban homes made out of wood could play a vital role in climate change mitigation due to their long-term carbon storage potential,” Mishra said, but, “Strong governance and careful planning are required to limit negative impacts on biodiversity and to ensure a sustainable transition to timber cities."

PIK’s researchers outline the necessity of policy to avoid land competition with agriculture and food production, and recommendations to ensure possible timber plantations don’t infringe on land deemed ecologically significant.

In fact, they conclude that timber cities are possible to meet growing urban housing demand but the production of timber from natural forests needs to be minimized or avoided completely. Frontier forests, biodiversity hotspots, and land earmarked for protection by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) need to be strictly prohibited.

"The explicit safeguarding of these protected areas is key,” co-author of the study Alexander Popp said, “but still, the establishment of timber plantations at the cost of other non-protected natural areas could thereby further increase a future loss of biodiversity."

Due to worries like these, the management of privately owned forests in places like California, Washington, and Oregon are highly regulated, not only to ensure their biodiversity but because these forests provide 75% of the water supply in the West. Research from Oregon State University, supported by the state’s Department of Forestry shows that scaling mass timber can strengthen these regulations.

The Oregon State researchers break down the rules and regulations around mass timber projects, safeguards for market demand, threats of deforestation, forest ownership, and carbon sequestration, arriving at the same solution as PIK: Sustainable mass timber is possible with the right regulations.

In the case of the Mass Timber Coalition's restoration funds, designated money will go to the Willamette National Forest. But the possibilities between forest restoration and mass timber don’t end there.

In Oregon and across the West, forest restoration projects are often aimed at wildfire mitigation. The byproduct of these mitigation practices is small logs that when banded together, can create vast slabs of mass timber. Additionally, Oregon State’s research points out that mass timber gives the incentive to keep forests healthy while providing emergency housing, creating what they refer to as a “forest restoration supply chain.”

“We are going to use the material that’s causing the wildfires, make the forests safer, and put it through industrial processes and then reuse it,” Professor Lech Muszynski of Wood Science and Engineering at Oregon State said in a video explaining the process. “It drives costs, will allow more projects to happen, and will allow more of this low-volume material to be used.”

He goes on, “So it is a cycle that feeds itself. Not only do you make the environment better, you make our part of the world safer, and you address perennial, societal problems at the same time. Isn’t it beautiful?”

Часом знаходжу цікаві сайти — випадково або коли хтось ділиться в чаті. Частину зберігаю про запас, іноді повертаюсь до них при нагоді. Тут є різне — новини, блоги, локальні стрічки чи просто незвичні штуки. Деякі переглядаю рідко, деякі — коли хочеться вийти за межі звичних джерел. Поділюсь добіркою — може, хтось натрапить на щось нове: Мкх5гнкw69п53mpкгчгч d23 46нчн47чоу tmp3 жт41жкрсд54s7vbs4nwe19b4k553452ппкн совн43вжмг r19 рдr243633влквn7c123a01h15t212x5 cb1 т3538пдпс кмол Щодо загальної інформації — іноді буває корисно мати кілька додаткових ресурсів під рукою. Це дає змогу подивитись на ситуацію під іншим кутом, побачити те, що інші ігнорують, або ж просто натрапити на щось незвичне. Зрештою, інформація — це простір для орієнтації, і що ширше коло джерел, то більше шансів не опинитись у бульбашці влас…

Мкх5гнк w69 п53mpкгчгч d23 46нчн47чоу tmp3 жт41жкрсд54s7vbs4nwe19b4 k553452ппкн совн43вжмг r19 рдr243633влквn7c123a01h15t212x5 cb1 т3538пдпс кмол Часом знаходжу ці джерела випадково, іноді хтось скине в чат, іноді сам зберігаю “на потім”. Частину переглядаю рідко, частину — коли шукаю щось локальне чи нестандартне. Вони різні: новини, огляди, думки, регіональні стрічки. Я не беру все за правду — скоріше, для порівняння та пошуку контрасту між подачею. Можливо, хтось іще знайде серед них щось цікаве або принаймні нове. Головне — мати з чого обирати.